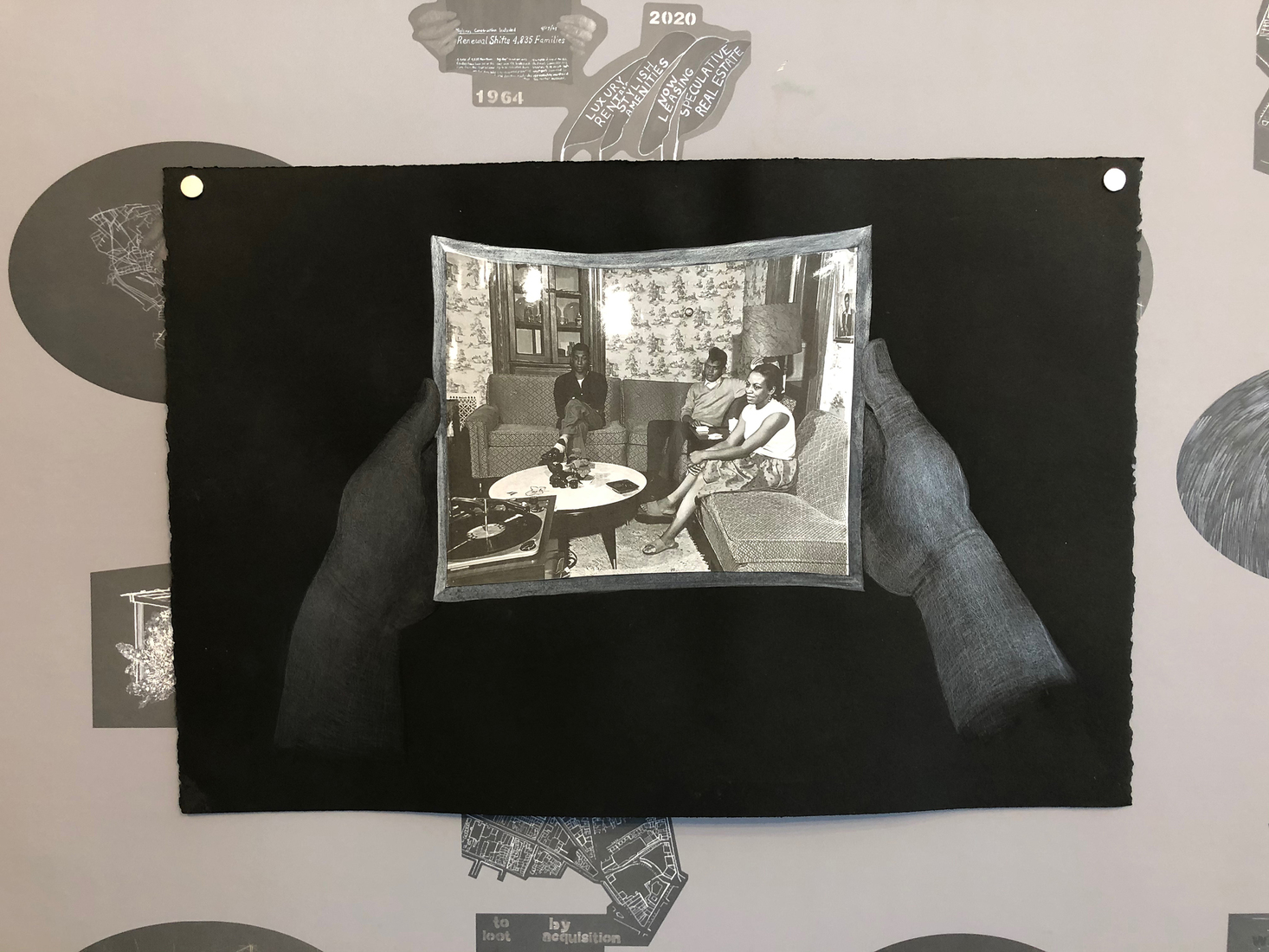

At a glance, the black and white photo appears to be an average midcentury family snapshot. Three nicely dressed people, expressing varying degrees of enthusiasm, sit in a homey living room surrounded by trappings of a middle-class life: plush couches, a record player, knick knacks on the coffee table.

But the appearance of cozy normalcy belies a darker purpose: taken by the local Housing Authority in New Haven, Connecticut, the image was staged as part of a collection documenting the mostly Black families being evicted from buildings set for demolition as part of the city’s “urban renewal” efforts. The government promised to responsibly relocate residents (the ostensible purpose of the photoshoot being to demonstrate their happy compliance with the plan) but that never happened.

When the artist Alex Callender came across this loaded image while doing archival research, she knew this history lurking behind the camera. But examining the scene more closely, she noticed a trace of it inside the frame as well. The living room wallpaper was a classic New England toile: a decorative, repeating pattern depicting pastoral and agricultural scenery of the American 17th century.

Callender, whose exhibition A Place for Not Forgetting opens at Northeastern University’s Gallery360 on June 28, saw the traditional wallpaper as a physical remnant of the image’s otherwise invisible narrative of dislocation, tracing a direct line from the seizing of indigenous land by British colonizers to the displacement of Black communities by the U.S. government. The history was literally in the background.

“It seemed like a place of intervention in an artistic sense, these stories that were embedded,” says Callender, who has exhibited internationally and lives in western Massachusetts where she is an assistant professor of art at Smith College. She created a new kind of wallpaper in History Constructs the House that Sometimes Holds Us (2020), comprised of 17 drawings replacing the colonial imagery of a traditional toile with the history of Black displacement and resistance.

This and other recent work will be on display in A Place for Not Forgetting through October 22, 2022, along with new work based on research conducted in the fall of 2021, when Callender was a fellow at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, in Harlem. The artist grew up in New York City and says being back in her hometown highlighted the need for restored narratives connecting the city’s current housing crisis to its history of injustice. “I grew up in a place where the effects of a housing crisis were so visible to me, and yet I didn’t know these histories,” she says of the materials she discovered at the Center. “It seems like we’ve lost the memory. And that enables it to happen again.”

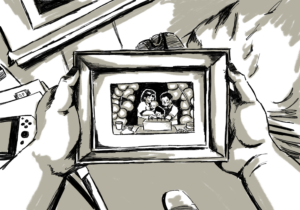

To resurface the memory, Callender redraws scenes from the archives, like a 1948 photo of a single woman. “She was totally dislocated from her community and becomes just the subject of an eviction,” says Callender. “We don’t know who was there to hold her on the other side.”

But in her drawing, part of the in-progress series Collect All the Waters that Fall Through Architecture of Memory (2022), Callender is less interested in dwelling in that painful unknowing than in supplanting it with the simple, yet radical hopefulness of individual narrative. With caring attention to the personal objects and family stories hidden in the bureaucratic nature of the image, she reimagines the woman’s apartment as a place of repair. “What if,” she wonders, “instead of tearing down buildings and abandoning the promise of public housing, the state just fixed her house like they said they would?” It’s a simple, hypothetical question with complicated answers in the form of real people’s lives.

The inclusion of wood in Collect All the Waters also underscores the material reality of displacement. Paper, too, is a symbolically rich medium for Callender, a “speculative place.” “It’s the language of bureaucratic violence and a tool of coloniality, and yet it feels very democratic” she says. “There’s this possibility of dreaming back into it.”

Callender hopes that audiences will join her in this process of speculative dreaming. She plans to work with the NU Law Lab and Northeastern faculty in public policy and architecture to develop programming that will help create larger contexts of the inequities contributing to housing injustice today. These collaborations will widen the impact of the exhibition, says Center for the Arts Director Juliana Barton. “We are thrilled to bring Alex to Northeastern,” Barton says. “Alex’s work will help deepen vital conversations about housing that are particularly pressing in Boston, given our current housing crisis.”

The artist believes this process of collaborative dreaming is not just about remembering the past or waiting for some ideal future state. It’s about our current moment. “We can reconcile these histories,” she says. “We can decide that housing is a human right. We can change.”

A Place for Not Forgetting is on view June 28 through October 22, 2022. An opening reception featuring a talk by the artist will be held on June 28 at 5 p.m. and is open to the public.

To schedule visits and tours, contact Center for the Arts Director Juliana Barton at [email protected]