By

Cody Mello-Klein

Department

Journalism

Share

By: Cody Mello-Klein

You’re walking down the hallway of your school, flanked on both sides by rusty, dented lockers. You stop to chat with your friends for a bit, but the school bell cuts your conversation short. Time for class.

As you begin walking to math class, a tall, menacing figure steps in your way. You try to side-step him, but he refuses to let you move past. He reaches behind his back and pulls out a pistol. It doesn’t seem that out of place here, but you wonder how he got it past the metal detectors at the school entrance.

Before you can say anything, he points the gun at you and yells, “Yo dude! Your cuz part of the Stones. You gonna dis them man or else.”

How do you respond?

This is one of the first scenes in We Are Chicago, indie developer Culture Shock Games’ narrative-based adventure game all about living and surviving in Chicago’s South Side. Using the real stories of residents of a South Side neighborhood called Englewood, Culture Shock Games has created a game that sits at the intersection of video games, journalism, documentary filmmaking and activism.

For many people whose only exposure to video games is big budget, so-called AAA titles like Halo, Grand Theft Auto or Call of Duty, We Are Chicago might seem like an odd duck. And for the most part it is. The game lets players take on the role of Aaron, an Englewood teenager dealing with the push and pull of family, school and gang life.

Over the last couple of years, developers have been fusing the research and process of journalism with the kind of interactive storytelling that games do best in order to create unique and moving experiences. We Are Chicago takes full advantage of the empathic potential in video games by allowing players to live in someone else’s world.

Culture Shock Games are certainly not the first to address real world issues in a virtual setting. Games like Gone Home, That Dragon, Cancer, and Never Alone, which were are released with the last two years, have tackled topics as diverse as a young girl’s sexual awakening, the traumatic loss of one family’s baby boy and the preservation of Native American stories and culture. However, even with all those big, overarching themes, these games have relied on empathy and immersion in order to tell heartbreakingly personal stories.

A screenshot from We Are Chicago. Credit: Culture Shock Games.

A screenshot from We Are Chicago. Credit: Culture Shock Games.

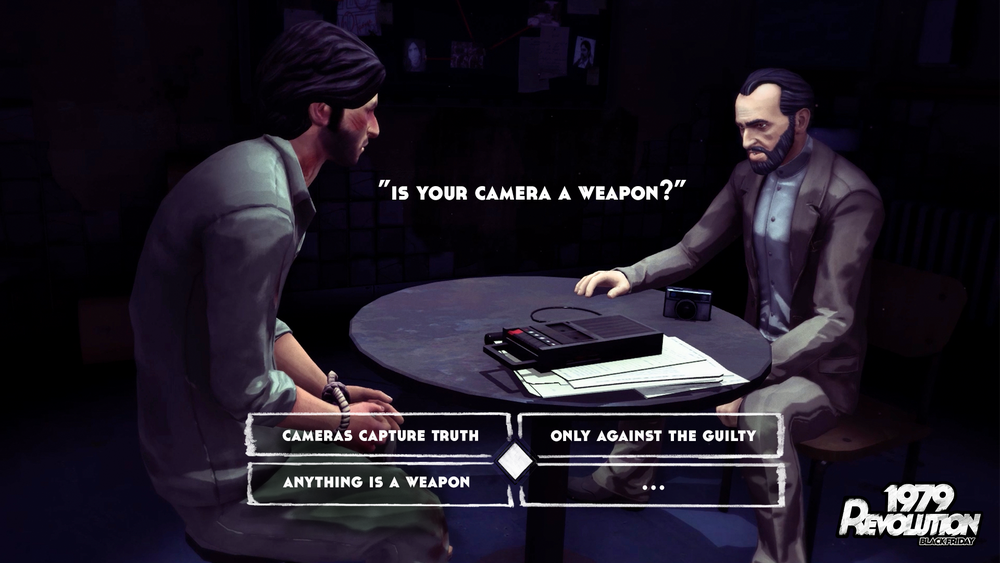

One of the more successful games to come out during this period was iNK Stories’ 1979 Revolution: Black Friday, which came out in April 2016. Based on the events of the Iranian Revolution, 1979 puts players in the shoes of Reza Shirazi, a photojournalist who returns to Iran as the revolution is starting to heat up. Players can interact with their surroundings, take pictures of certain people or events and make choices in dialogue or actions that impact the narrative.

iNK Studios used the Telltale Games approach to narrative-based adventure games as a foundation for gameplay, however the core of the story remained in the interviews the team did prior to starting development.

A screenshot from 1979 Revolution: Black Friday. Credit: iNK Studios.

A screenshot from 1979 Revolution: Black Friday. Credit: iNK Studios.

For some people on the team, the intense amount of research and nearly 40 interviews was a challenge. For Sam Butin, cinematics producer at iNK Studios, that process was absolutely necessary for the story the team wanted to tell.

“We didn’t want to craft a narrative that had some extreme bias to it,” Butin says. “We tried to get a wide array of cultures and classes, a wide array of perspectives on the revolution.”

While most game developers would have trouble even starting the interview and research process, iNK Studios was different. Many members of the team, including Butin, came from backgrounds in film and documentary filmmaking in addition to game design. Game director Navid Khonsari, who had almost 20 years worth of experience in the games industry, grew up in Iran during the revolution, which provided a strong cultural backbone for the project.

But even with all that knowledge, a lot of the interview subjects were unsure about the project. Not only was it a game, which many dismissed outright, it was a mostly Western development team trying to tell an Iranian story.

“People were naturally skeptical…they had seen other examples in Western media,” Butin says. But in the end most of them ended up lending their stories to the game.

Those interviews were the building blocks with which iNK Studios built their story. Unlike in journalism or documentary filmmaking, 1979 was a story based in fact but stretched to accommodate for a dramatic narrative. That still meant the team, like most journalists, had to be careful with how they used the testimonies of their interview subjects.

One of gaming’s greatest strengths is interactivity. With 1979 the team could create a living, breathing world – “a place lost to time,” as Butin called it – that had the factual strength of journalism and the complex, emotional decisions of a video game.

That’s where a simple but impactful line of dialogue – “Your cuz part of the Stones. You gonna dis them man or else” – can work wonders.

That one line was the result of a lot of hard work on the part of Michael Block, lead designer at Culture Shock Games, and the rest of his team. We Are Chicago, which Culture Shock Games released in February 2017, takes a very similar approach as 1979, but the team’s lack of experience with interviews or research made the development process even more difficult.

“We aren’t from that background so interviews aren’t something we’re used to,” Block admitted.

Despite their lack of experience, the small team at Culture Shock Games dove right into interviewing Englewood residents. They started by doing short five-minute interviews to get the broad narrative strokes of each person’s life, before they did their in-depth follow ups. It was in these interviews that Block and his team “really drilled down into the details,” Block says. Without any experience with interviewing sources, Block slowly but surely learned how good interviews come out of both directed questions and on-the-scene discoveries.

Block also made sure to contact and work with people and organizations, like writers, academics and non-profits, who came from backgrounds other than game design. “Find other people who are interested in this in other disciplines and get them involved…Seek out people who have the experience you don’t have,” Block says, encouraging other developers to do the same.

Like with iNK Stories, all that work informed the game and the authenticity of the storytelling. “If you want to make believable characters and compelling characters a lot of that comes out through in depth research initiatives,” Block says. The team built characters and scenes on a foundation informed by the broad strokes of the interviews, but the small details that came out through peoples’ stories helped fill out the scenes.

More importantly, by really immersing themselves in the community and environment that they were recreating in virtual form, Culture Shock Games were able to see the intimate, personal side of a neighborhood that’s been reduced to homicide statistics in the news. In a lot of ways, We Are Chicago is a response to the way journalists have written about Chicago.

“One thing we were trying to say with the game is look, here are the things you see on the news all the time but there’s a personal side to it,” Block says.

By balancing the personal stories of Englewood residents with the broad Chicago narrative, Culture Shock Games ended up creating the video game equivalent of a features story.

Block and his team used the immersive nature of video games to force players to make decisions they wouldn’t normally make within the context of a life most people view as foreign.

“Our primary goal was to educate people about what’s happening…and to build empathy with people living in these situations,” Block says.

We Are Chicago, like 1979, is based around the player making choices in dialogue that impact the narrative and how other characters react to the player. Making tough choices like whether or not to confront a gang member forces players to think about themselves and others in new and meaningful ways that a non-interactive medium just can’t match.

That kind of storytelling challenges a medium that often relies on over-the-top violence and action, but many gamers have already found the approach rewarding.

Block recalled an incident when he realized the impact games like We Are Chicago could have on people.

“[Some gamers] were making really disparaging and insensitive comments towards the characters in the game,” Block says. However, they decided to try the game out and came away with a very different view of the people they had been insulting minutes before.

“They had to engage with them and talk with them as people,” Block says. “Knowing that the game can reach people on that level is amazing to see.”

Ultimately, both iNK Stories and Culture Shock Games wanted to have an impact. They wanted to tell powerful human stories in a medium that too often gets caught up in bombast and action. And while this kind of approach to socially conscious game development can bring critical acclaim, it doesn’t always result in sales.

Speaking to the current state of the games industry, Block says, “The audience for documentary games isn’t really there right now…we haven’t expanded the gamer audience to reach those people at this point.”

At the same time, games like We Are Chicago and 1979 couldn’t have been made at any other time. The industry is evolving to the point where even larger studios, like DICE and its World War I shooter Battlefield 1 – are experimenting with serious, research-driven narratives. Games aren’t just pure entertainment. In fact they haven’t been for quite some time. They can tell emotional stories, start thought-provoking conversations and address real issues.

But all of that requires hard work and the kind of attention to detail that journalists use every day. If developers continue to take this more grounded journalistic approach to research and development, collaborating with journalists may be a necessary part of the process. Although game designers have a lot to teach journalists about engaging with audiences in the digital age, it may be worthwhile reminding developers to make room for some shoe leather between all the lines of code.